With anti-racial protests and the ‘Black Lives Matter’ campaigns blowing like thunder in almost all the cities of the globe, fashion brands are also not exempted from the conversations. According to a research paper titled ‘Racism Untaught’, there are three elements of racism in design, identified as: artefacts, systems and experiences. The three areas include broader perspectives of Racialised Design which says designers possess the power and privilege to affect our society positively. It is crucial to incorporate these values into a ‘diverse pedagogy’which ensures that right from the curricula taught in design classrooms, designers understand the implications of their design on the culture and communities. An experiment was made to show that both the historical and contemporary directives of artefacts, systems and experiences, inculcated different forms of racialised design. The framework was curated for design educators to improvise the collection of the three categories in design methodology.

Moreover, the Kelly Initiative , which includes more than 250 black fashion professionals, sent a public letter to the Council of Fashion Designers of America(CFDA), accusing the organisation of permitting‘exploitative cultures of prejudice, tokenism and employment discrimination to thrive’and renounced a more robust plan of action of their own and focused on responsibility towards the society. Of all, social media has been the biggest booth for activist campaigns and get-togethers on the topic of racism. On Instagram, luxury brands from Gucci to Prada to Everlane to Reformation , have been posting content in their feeds, stories and comments voicing anti-racial campaigns.

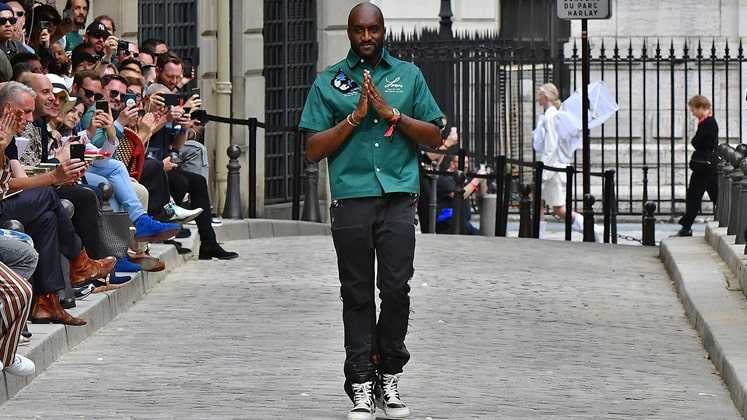

However, even today black representatives make less than 5 per cent of all the 500 invite-only members of the most influential trade organisation in fashion industry – the CFDA. The undeniable truth is that the fashion industry has a long history of writing black models, designers, photographers and business leaders off. Virgin Abloah , the first African-American Creative Director of Louis Vuitton , covered a major part of the headlines lately. Why is this lack of diversity so trickling in an industry which always speaks boldly on social equality issues? Aurora James , Founder of Brother Vellies , a luxury fashion brand, expresses that brands need to do more than just speaking over movements for racial justice.

The industry giants need to show up with better strategies to win over systemic racism in the United States. “I kept seeing brands post their support of Black Lives Matter, but as a black woman and a black business owner, I wasn’t really feeling it,” were her words. Further expressing her emotions as a black designer and entrepreneur she added, “I just didn’t get the sense that they truly understood what ‘standing with someone’ meant.” Aurora James has further introduced a ’15 Percent Pledge’ which calls out to retailers and brands to dedicate at least 15 per cent of their shelf spaces to designs made by black-owned design labels. Why 15 per cent? Because that’s the percentage of blacks in the US. The retailers include Target , Shopbop , WholeFoods , whom the designer asks to put their money where their mouth is.

One of the best-known US-based designers, Tracy Reese is also a member of the CFDA board. She came out straight and bold on the issue of racism in the industry. “I haven’t just thought about inequality in this industry—I’ve experienced it,” she said. Speaking of her experiences in the industry of over three decades, she expressed, “For my generation, there wasn’t time to stop and register racial injustice. There was really much more of an attitude of bearing down and walking around to achieve your goals.” Reese applauds the spirit of today’s generation of designers and fashion professionals who are not willing to tolerate injustice. She says, “Instead of operating within a flawed system, they are demanding that the system itself should change.” Further she admires that the brands are showing their enthusiasm to change the system but warns that it demands holding one’s feet on fire and staying true to what their words are promising.

An example of a revolutionary approach establishing in the industry, 29-year-old Anifa Mvuemba has constructed her own fashion line named Hanifa going out of the box. She encourages other black designers to follow the same path, in order to promote equality. Rather than moving to New York, Mvuemba, she headquartered her eight-year-old design house in Maryland, her motherland. Surprisingly, she has built this US $1 million business without attending an international fashion school or interning for a big designer, nor has she showcased her collections at the New York Fashion Week at any time. Her designs are popular among celebrities from Lizzo to Kylie Jenner .

Like many other non-white strugglers, she found this pre-inclined world too intimidating. “As much as I wanted the fashion world to recognise what I was doing, it seemed impossible,” she says. In line with her work and success she has made, Mvuemba points out that one reason behind the struggle of black designers is the traditional route taken to break into the industry, which involves moving to the white-dominant cities and trying to build connections within a small group of encouraging people who are industry insiders. “I saw other [nonblack designers] launch their businesses five years after I did, and boom! They seemed to break in so much more easily.”

Undeniably, the world of fashion has been equally challenging as well as protesting for the black professionals. No matter whether the brand is owned by whites or blacks, the clothes we wear involve millions of black and brown people as employees and as workers in the factories. Practices involved in buying of fast fashion products turn a blind eye towards malpractices in labour sourcing and allowance of unpaid or forced overtime at developing sourcing destinations. The current models used by brands in controlling production keep the garment workers working in poor and unhygienic conditions to maximise their own profit margin. These practices have leveraged the gradual erosion of apparel labour rights by manufacturers and the governments. As a legacy of colonialism, economic exploitation caused by fast fashion manufacturing is still prevalent in the industry.

Thus, there is a need to address a lot more issues relying on racism other than those which are visible on television and social media.

Post a Comment